When discussing artificial light, the questions “How far from the lights should the plants be?” and “How large of an area can they cover?” come up frequently. Those are, unfortunately, not really simple questions to answer.

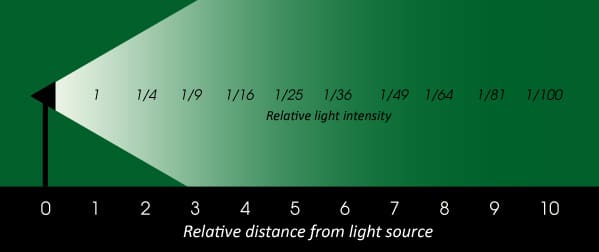

First of all, we must remember that light intensity drops off as the inverse square of the distance. In other words, doubling the distance from the light source decreases the light intensity to one-fourth of what it was, and tripling the distance drops it to only one-ninth, and so-on, as depicted below.

As the inverse-square law applies to relative distances and intensities, we could just as easily start our measurement at the arbitrary “3” in that diagram, meaning that the intensity at “9”, being three times the distance, would have 1/9th the intensity as at the “3”. The implication to plant lighting, therefore, is that by using light sources of different intensities, you can match the light levels to your growing area. For example, if light source “A” has the same intensity at one foot distance as light source “B” has at three feet, then the light intensity for “B” at nine feet is equal to that from “A” at three.

Another aspect of the inverse-square law is that it applies to light radiating in all directions, so the points of equal intensity form a sphere with the light source at its center. That is important to us because the floors and table-tops we grow our plants on are not curved like the surface of a sphere, so if our light source is positioned directly over a round table, for example, the light intensity would decrease as you move from the center to the edge of the table.

That is all fine and well, but most bulbs do not emit light from a single point, and it and the diagrams above do not take into account the effect of a reflector.

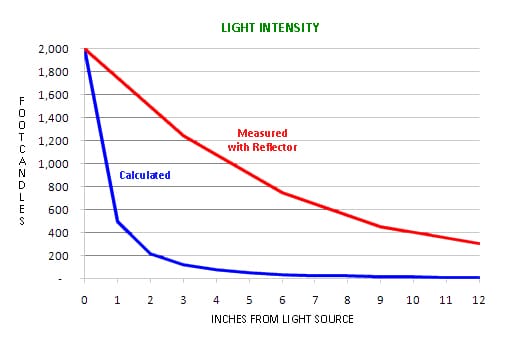

In the case of a single fluorescent tube, the “point” light source becomes, in essence, a “line” of light, so it takes that circular light distribution and “stretches” it into an elongated shape with rounded ends. One might also argue that the longer length of a fluorescent tube might “reinforce” or “strengthen” the light intensity under the bulb, as the light emitted from the middle of the bulb is reinforced by the light spreading from the points on either side of it, plus that coming from a little farther out, plus a little farther out from that, etc., etc. (We’ll return to this in a moment.)

Reflectors on lights are both limiting and intensifying. Limiting, in that they block the rays from escaping from all directions for the light source. That’s actually not all bad, as often a well-designed reflector cuts off the light that would be of practical use to the grower. Referring back to the diagram above, a decent reflector might limit the rays to the area within the legs of the table.

But a reflector can also be a HUGE addition, as it can reflect and redirect the light that would be lost upward and to the sides, down toward the plants. The graph below shows what would be the calculated inverse-square drop-off in light intensity from a single-bulb 24-watt, two-foot T5 light fixture, plus the actual light meter measurements, that clearly show the effect off the reflector coupled with the “line of light” effect mentioned earlier.

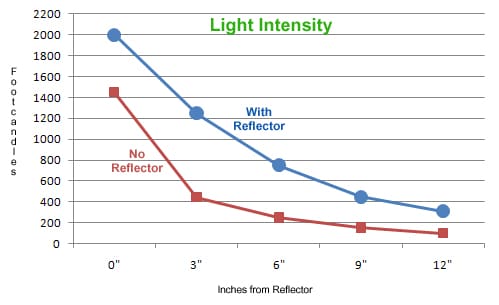

To show that the improvement was not entirely from the reflected light, the graph below shows the same fixture with the reflector removed. The blue line in this graph – “with reflector” – is the same data as the red line above, and it is clear that the “no reflector” curve still shows an improvement over the calculated light intensity curve, above.

To show that the improvement was not entirely from the reflected light, the graph below shows the same fixture with the reflector removed. The blue line in this graph – “with reflector” – is the same data as the red line above, and it is clear that the “no reflector” curve still shows an improvement over the calculated light intensity curve, above.

We have not addressed the use of multiple bulbs, but that’s simply a multiplier to the information above.