Nomenclature

There are basically three aspects of nomenclature that may come up when reading or discussing orchids:

- Orchid Naming Nomenclature

- Inflorescence types (they’re not all “spikes”)

- Shape & Structure Nomenclature

We will address them individually, below.

Orchid Naming Nomenclature

All plants and animals may be classified using the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature. Without going through the entire structure, we can say that all orchids belong to the Family Orchidaceae, and are grouped below that into various subfamilies, tribes, subtribes, and so on. It is the next level down – the genus – upon which we concentrate. The following sections delineate the proper way plants’ names should be documented, and will help you understand exactly what that tag says:

Species

Cattleya intermedia var. coerulea subvar. aquinii ‘Big Blush’

Cattleya – genus

- Latin

- Italicized

- Capitalized

intermedia – species

- Latin

- Italicized

- Lower case

coerulea – variety

- Latin

- Italicized

- “var” not italicized

- Lower case

aquinii – subvariety

- Latin

- Italicized

- “subvar” not italicized

- Lower case

‘Big Blush’ – cultivar (sometimes called “clone”)

- Enclosed in single quotes

- Not Latinized

- Capitalized

- Not italicized

Artificial Hybrids

Phalaenopsis Sweetie Bear ‘Sara Jane’

Phalaenopsis – genus or hybrid genus*

- Latin

- Italicized

- Capitalized

Sweetie Bear – Grex (hybrid name)

- Not Latin

- Not italicized

- Upper case

‘Sara Jane’ – cultivar

- Enclosed in single quotes

- Not Latinized

- Capitalized

- Not italicized

* While in this hybrid example, phalaenopsis was the genus of both parents, hybrid-generic names are used when more than one genus is involved in the breeding. Often, in combinations of two or three genera, the names are combined, such as doritaenopsis (a cross between doritis and phalaenopsis) or sophrolaeliocattleya (sophronitis, laelia and cattleya). When the hybrids get more complex, it is common to name the multigeneric hybrid after an individual, attaching an “-ara” to the end, as in potinara (cattleya, brassavola, laelia, and sophronitis).

Unnamed Hybrids

If a cross has been made, but has not been raised to blooming and registered with the International Orchid Registrar, it is common to simply list the parents.

Pescatorea lehmanii X Cochleanthes River’s Edge

The female parent (also known as the capsule- or “pod” parent) is listed first. Additionally, if the cross involves plants of the same genus, it can be listed once, simplifying the name, as in Paphiopedilum bellatulum X delenatii. Sometimes those are enclosed in brackets – Paphiopedilum (bellatulum X delenatii).

Note that if this hybrid does get registered and named, both it and the reciprocal cross Cochleanthes River’s Edge x Pescatorea lehmanii will have the same grex name.

Natural Hybrids

These are naturally occurring hybrids from locations where populations of similar plants overlap. They can be either interspecific, within one genus, or intergeneric, between species of different genera. The “X” that designates the plant as a natural cross, is often left off.

Interspecific: Paphiopedilum X wellesleyanum (Paph. concolor x godefroyae)

Paphiopedilum – genus

- Latin

- Italicized

- Capitalized

X wellesleyanum – grex

- Latin

- Italicized

- Lower case

Intergeneric: X Dactyglossum mixtum (Dactylorhiza fuchsii x Coeloglossum viride)

X Dactyglossum – Hybrid genus

- Latin

- Italicized

- Capitalized

mixtum – hybrid

- Latin

- Italicized

- Lower case

Note that very often the “X” is left out of the name of natural hybrids, which is supposed to be reserved for the man-made equivalents.

Use in Writing

When referring to a particular plant, capitalize the genus as stated above. If, however, you’re referring to a group of plants, the genera are not capitalized. As an example: “Of all of the vandas and ascocendas in my collection, my favorite is Ascocenda Princess Mikasa.”

Awards

You will sometimes see some random-looking letters after the complete name of the plant, usually something like “AM/AOS.” That is an indicator that the particular plant (or it’s grower, in the case of a CCM) has met or exceeded certain standards and has been given an award. The characters before the slash tells the award, and those after tell the issuing authority. The more common award levels are:

- FCC – First Class Certificate

- AM – Award of Merit

- HCC – Highly Commended Certificate

- JC – Judges’ Commendation

- AD – Award of Distinction

- AQ – Award of Quality

- CBM – Certificate of Botanical Merit

- CBR – Certificate of Botanical Recognition

- CCM – Certificate of Cultural Merit

- CCE – Certificate of Cultural Excellence

- CHM – Certificate of Horticultural Merit

- GM – Gold Medal

- SM – Silver Medal

- BM – Bronze Medal

The issuing authority of the award may be a society or other convention of interested parties. Those include, but are not limited to:

- AOS – American Orchid Society

- RHS – Royal Horticultural Society

- HOS – Honolulu Orchid Society

- JOS – Japan Orchid Growers Society

- JOGA – Japan Orchid Growers Association

- WOC – World Orchid Congress (preceded by the number of the congress)

When a plant gets multiple awards from the same society, or the same award from more than one society, hyphenation is used: CBM-AM/AOS, or FCC/AOS-RHS.

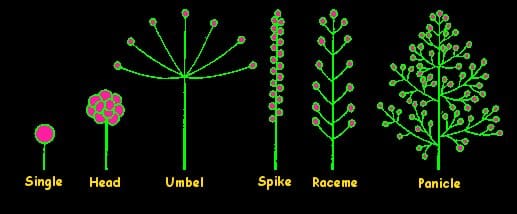

Inflorescence Types

Those of you who frequent the rec.gardens.orchids newsgroup, the various orchid forums, or subscribe to orchid-related mailing lists have probably run across discussions relating to the proper terminology for the inflorescences our plants display. Most of us simply refer to them as “spikes,” but that’s not really accurate. The diagram below ought to help us all.