Sphagnum Moss – Friend or Foe?

If you’ve worked a lot with various potting media, you’ve probably had some experience with sphagnum moss. It is a great additive to drier mixes if you need to enhance the moisture-holding capacity, and it is an absolutely fantastic medium for a wide range of orchids if used all by itself.

However, there seems to be a great deal of variability in opinions about it, it’s quality as a medium, and folks’ success in using it. In this article, I’ll try to provide a little insight into the material itself, why it’s great for some and a killer medium for others, and maybe lend a trick or two to making it work better for you.

The first thing to understand is that not all sphagnum is created equal. Sphagnum is a genus of peat mosses comprised of as many as 300 species (or more, depending upon the taxonomist). They vary all over the map in terms of their color (almost white, to green, pink, and even red), their habitats (valleys, mountains, aquatic, terrestrial), and physical structures. It is the last of those that is of primary importance to the orchid grower.

The most common species used as orchid-growing media and basket liners are Sphagnum cristatum and S. subnitens, particularly those found in New Zealand, but others, like S. magellanicum from Chile are also used, as are others harvested wild and farmed throughout mountainous regions of South America and elsewhere. Some authorities will tell you that certain species are better than others – which is generally true – but there is enough variability within the growth of any species that there is considerable range and overlap in quality – and price.

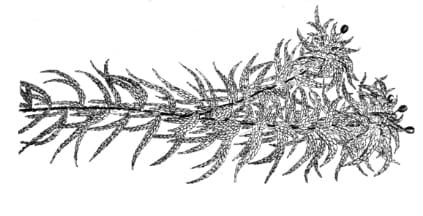

Looking at the structure of sphagnum, it grows as a strand surrounded by “fluffy” fibers, as shown in this botanical drawing:

The length of the individual strands, and the length, thickness, and density of the fibers all affect the absorption and “springiness” of the moss, with long, thick, and dense strands being the best.

Shifting briefly to what is important to orchid culture, we know that in addition to holding and providing moisture to the plant, the potting medium needs to stay open and airy to allow the plants’ gas exchange processes to carry on freely via the root system. That is the crux of the “sphagnum conundrum” – packing it firmly enough to secure the plant, without suffocating it – and “what works” is determined by the quality of the moss, the pot, and the growing conditions.

The dried moss, by itself, is a pretty good “sponge”, absorbing and spreading water uniformly throughout its tissues, which is what makes it such a great potting medium. However, when we pack the moss somewhat tightly, we make the spaces between the fibers smaller. Just like using a fine bark, or letting a potting medium decompose, that allows water to be trapped by surface tension and fully fill the spaces, resulting in the “soppy mess” most folks (and plants!) object to. However, and this is something that is a bit counterintuitive, if the moss is very compressed, it actually can hold less water in between the strands, making it great if your conditions lead to rapid drying.

Another issue that folks using sphagnum run into is the fluffy mass becoming more-and more dense with time, particularly if heavy watering from overhead is the norm, and with the use of lesser-quality moss.

So why is it that some growers – notably some of the “big name” commercial growers in Hawaii – seem to do so well with very tightly-packed sphagnum?

One factor is their use of premium, “5-star” New Zealand moss. Having very long stands and being very fluffy, even when firmly packed around the plant’s roots, there is still a considerable amount of air space in the mass. Its sturdy structure also “holds up” better under the weight of the absorbed water, so won’t collapse as readily. Add to that the fact that their dynamic growing environment (lots of sunlight, air movement, and an overall buoyant atmosphere) fosters pretty rapid drying, and problems with extended, waterlogged pot conditions are minimized. Move those same plants into my greenhouse environment, and it’s “dead roots” time. (Another, less-discussed factor is that of time – plants don’t stay in their care for very long, so the moss never has time to break down.)

With the less-than-ideal growing conditions most of the rest of us have, what can we do to get the benefits of sphagnum while avoiding – or at least delaying – the pitfalls? Here are a few of the tips I’ve learned over the years:

Use top-quality moss. It is far more forgiving of misuse than are lesser grades.

Learn to water lightly, merely moistening the moss, rather than “smashing” it down with heavy overhead watering. (A quick aside here: the “ice cube” watering trick addresses that well. You may not like the concept of ice on a tropical plant [I don’t], but the slow melting of the cubes does achieve a slow, non-compressing watering technique!) One trick I’ve learned is to place a 1″-2″ layer of LECA at the bottom of the pot, with the plant and moss on top of that, then only water from below. The LECA absorbs and wicks the water up to the moss, which becomes uniformly moist without ever being mechanically disturbed.

Consider blending the moss with more “rigid” components. I have had success with coarse strands of coconut husk fiber, interwoven with the strands of moss, as well as perlite or charcoal – anything that helps the sphagnum “stand up” under its own wet weight.

Do some experimenting. Once you gain a reasonable level of “mastery” of the moss, you’ll find it to be a good addition to your orchid-growing arsenal. Yes, it will always be one of the shortest-lived potting media you’ll use, but the phenomenal growth rate is often worth the more-frequent repotting.